I Said YES to Evolving Professionals

A magical moment last summer: within moments of saying “no” to some work, an opportunity for a big “YES!” arrived only hours later.

I’ve long struggled with figuring out where I fit in the planning profession. What has been clear all along is that few people recognize and appreciate what I offer to them, their teams and their work. Also clear: when they reach out to say, “let’s figure out how to do something together,” we end up doing fantastic, game-changing work together. I’ve learned to trust that every time I say no to work, I’m making space in my life for the work that energizes me—and the people I work with.

The “no”

The “no” I voiced was to professional colleagues who wanted my insight and skills on their project: a conference to talk about evolution in the planning profession. I was immediately intrigued because if you’re going to put “planning” and “evolution” together, I want to be in the room. We went back and forth to explore how I could uniquely support their desire to create a gathering around that word, “evolution.” In the end, they wanted my services to a point; they were not willing to pay.

On the surface, I said no to unpaid work. Below the surface, I also said no to supporting an event that did not create the conditions for our profession to evolve.

The “YES!”

Mere moments after my no to the conference organizers, I got a call from a planner leader (I’ll call them Chris) working in a North American city government. Chris and their colleagues were up against the wall, beaten down with the failure and unpopularity of recent projects with both elected officials and residents. They were licking their wounds, feeling bad, and recognized that they needed to revisit everything about their work.

Chris recognized that the ways they work, and the deeply ingrained ways they work, are no longer working. They need to find a new way to serve their city, and they don’t know how to do it. They asked for help.

The key ingredients for me are that they recognized that:

What they do is not working

How they work is not working

Who they are is not working

Chris asked me to help their team of 40 planners to have a conversation about failure, what they know about themselves because of failure, and who they choose to be due to what they know now. Chris identified an opportunity for their colleagues to explore new possibilities for their work and their city. They were choosing to create the conditions for themselves to learn and grow. They would pay me. Perfect.

Let’s talk about evolution

I have a deep desire to create the conditions for cities to evolve. For me, this means making conscious choices, rather than unconscious choices, about how to improve our communities. So when we gather to learn about our work and what we do, we need to create social habitats that foster our growth and development, not leave it to chance.

That “no” was about more than being paid for my work. When people are waffling about whether they want my services or not, how they handle my fees reveals where they stand. If they want my contribution, the client pays me without question. (We might negotiate scope to fit their budget, but that’s the extent of the negotiation.) If they do not want my contribution, they resist payment. Whether the other wants my contribution or not, or wants to pay me or not, isn’t good or bad; it’s a way to measure alignment between us. While we may not have been clear about what was out of alignment, the result was insufficient alignment between the conference organizers and me, so we parted ways, wishing each other well.

Energetically, that “no,” for me, was about the work I want to do: to evolve the work that planners, communities, builders, citizens, and governments do together. My remit is to set the table, to create the conditions, for people to think new things——a prerequisite for evolution—and make and do new things. My remit is not to set the table for more of the same.

“That “no,” for me, was about the work I want to do: to evolve the work that planners, communities, builders, citizens, and governments do together.”

The conference organizers were stuck in a familiar place: the conventional conference where we predetermine who will talk about what for everyone else to listen to, weeks or months ahead of time. This is like land use zoning, where we predetermine who can build what, where, how tall, how far from property lines, and what people can do in what they build. Planners are comfortable being prescriptive, but prescription minimizes the opportunities for new possibilities.

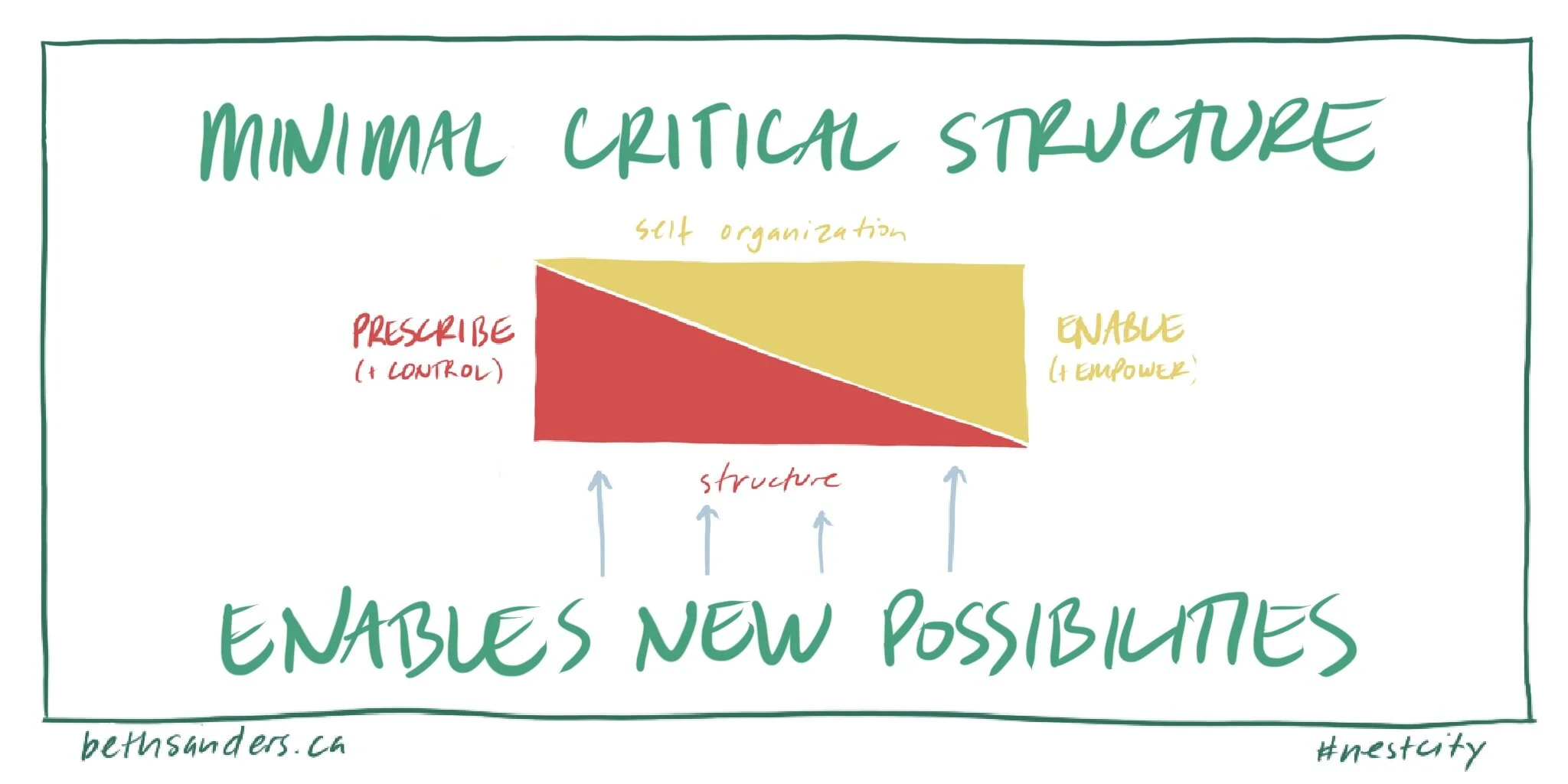

Evolution needs new possibilities. Too much prescription, at a conference or in a zoning bylaw, limits our creativity and leads to confusion (think of an overly complicated conference program or zoning bylaw). Too little prescription leads to instability and incoherence.

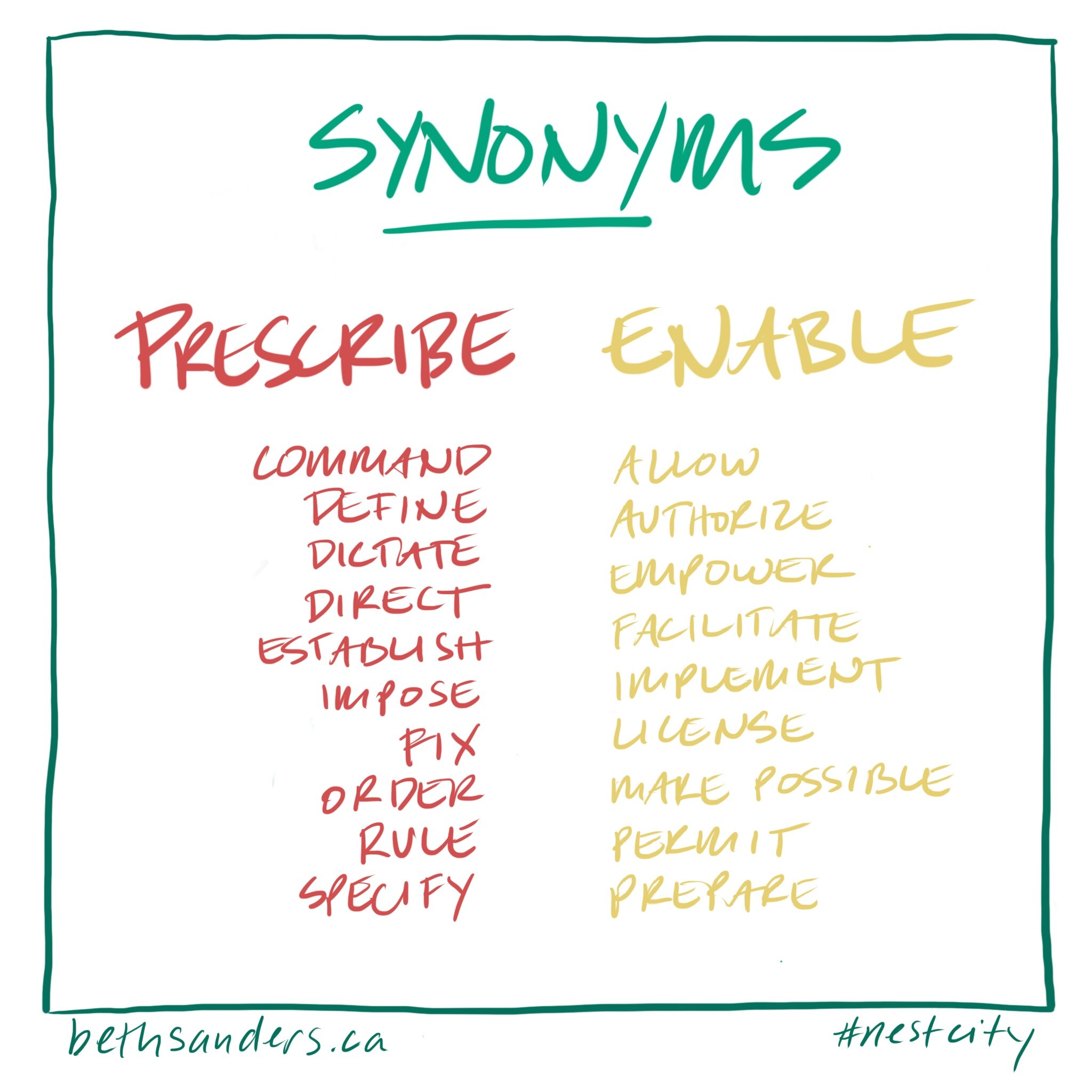

Where “to prescribe” is about control, at the other end of the spectrum is “to enable,” about empowerment.

Prescribe AND enable

We don’t have to choose between prescribe OR enable. We need to decide how much of each suits the circumstances. They are co-existing polarities.

The question I always ask is not, “What is the right amount of structure?” I ask, “What is the minimal critical structure?”

The contrast between prescribe and enable

Let’s take two familiar examples for planners and citizens alike, a zoning bylaw and a conference, to compare the polarities of prescribe and enable.

In a zoning bylaw:

Prescribe (control): We’ll tell you what you can build and do (choose from this list), or

Enable (empower): Get creative and do what you want (within these reasonable constraints).

At a conference:

Prescribe (control): We’ll tell you what you can do or talk about (choose from this list), or

Enable (empower): Talk about or do what energizes you with whoever you want (within this theme to help focus our conversation).

Prescribe and enable have their own feel, their own energy, because they have different purposes. They are each appropriate in different contexts. For example, prescribing with rules and commands makes perfect sense in city bylaws that regulate construction practices for life safety. In contrast, enabling by facilitating creative entrepreneurial efforts makes perfect sense for general retail services in the city. We do not need to regulate what a business makes and sells, provided that it is not criminal or has no unfortunate consequences for neighbours.

Each is appropriate in certain contexts. The context determines the right mix.

Let’s choose to evolve our practice

Planners like rules.

Planners enjoy the intellectual stimulation of layers of policies and rules, figuring out how policies work, don’t work, and how they guide efforts to stated outcomes. These planners can be working in the land development industry, economic development, social justice or ecological planning. We share a desire to document what is to be achieved and the actions needed to reach that achievement.

Planners like control.

Our training at school and in the workplace is rooted in the inertia of prescribe and control. This is our default stance.

When I started working as a planner in 1995, my boss pushed the boundaries of planning practice to create a “less prescriptive” zoning bylaw. In our case, it meant turning a 5-page list of commercial land uses into one half-page. The bylaw listed so many uses that we had to change the bylaw when a business proposed a new land use, a costly and time-consuming endeavour. My boss’ take: if it’s legal to sell, then our rules should not get in the way unless there’s something only we can regulate.

Citizens like rules too.

Whenever planners start talking about simplifying the rules, citizens jump up to say they want more regulations and a high degree of control over what happens around them. The conundrum: we citizens want rules for others, but not rules for ourselves. Pick any topic: some people want more rules, and others want fewer rules.

What are the rules for?

Figuring out the right rules for the right context is hard and messy work. It would be easy if planners could prescribe a set of rules and the city magically take that shape. City making does not work that way; the views of other folks at city hall come into play, as well citizens, community organizations and the business community. Planners play a significant role in bringing the parties together to sort out what rules are for, what works well, what does not, and how to improve them.

About a decade ago, the Alberta Professional Planners Institute identified new growth for the profession: critical thinking, professional and ethical behaviour, leadership, communication and interpersonal skills. (The old, conventional skills are writing and implementing plans and policies.)

Alberta Professional Planners Institute Competency Tree (Dark leaves: old growth. Light leaves: new growth.)

In the messiness of city life, among city planners and their colleagues at city hall, citizens, community organizations and the business community, we need clarity around the purpose of rules. We also need clarity around whether the policies and rules meet that purpose. To have these kinds of conversations, we need new skills that come to the fore only if we release our hold on to prescribe and control as individuals and practitioners.

5 new competencies

In addition to our content expertise, we need to cultivate our social habitat expertise by letting go of our heavy reliance on prescribe and control ways of operating and making space for enable and empower ways of being. I envision (at least) five new competencies for APPI’s competency tree:

Communicate with clarity and purpose

Create social habitats where conflict is explored and resolved

Enable the city to be in conversation with itself

Hold space for diversity, equity and inclusion

Host conversations that allow new possibilities

These competencies are for the official planners and anyone working with others to improve the city.

Our ability to learn these competencies is directly associated with our ability to learn new ways of thinking, making and doing. And our new ways of thinking, making and doing supports the evolution of our communities and cities.

Choices

How we relate to the rules associated with our work, to each other and the communities we serve, is a choice directly linked to the evolution of our professional practice, whether a professional planner or otherwise. When too reliant on prescribe and control we place a limit on our conscious growth and development. When we enable our capacity to empower ourselves and others, we remove, or at least raise, that limit on our conscious growth and development. If the contribution of our work is to improve our communities and cities, then these limits are not wanted.

The choice about bylaws:

Prescribe and control what we want in bylaws OR enable and empower what the community wants

The choice about how we talk among ourselves:

Prescribe and control by limiting what we talk about among ourselves OR enable and empower ourselves to explore and live into new possibilities

The choice about how we work with community:

Prescribe and control what we want the community to talk about OR enable and empower the community to explore and live into new possibilities by inviting them to talk about what they want to talk about

If we are not able to talk among ourselves in ways that allow us to explore and live into new possibilities, we will not be able to work on the content of our work, or our relationships with others in our communities, in ways that allow the voice of the community to emerge. “Prescribe and control” and “enable and empower” are embedded in the content of our work and how we talk about our work, with ourselves and others.

A quick participatory test

Here’s a quick participatory test to help you assess if the gathering you are planning or are participating in leans away from prescribe and control and into empower and enable.

Question 1: Are we spending most of our time focused on the words of one or a few people or the words of many people?

If few people: a prescribe and control habitat

If many people: an enable and empower habitat

Question 2: Are the topics, tasks and activities determined by the organizers or participants?

If organizers: a prescribe and control habitat

If participants: an enable and empower habitat

Question 3: Are the people we work with decided for us or chosen by us?

If decided for us: a prescribe and control habitat

If chosen by us: an enable and empower habitat

Active involvement in evolution

When I said YES! to Chris and their 40 planners, I was saying a resounding YES! to work with people who wanted to participate actively in their evolution as planners. They wanted to name and examine what is not working and actively improve their work and relationships.

The 40 planners named their evolution, from disjointed, confusing, uncoordinated and frantic work to something new. That “something new” is under construction at the moment, but here’s what I observed them say yes to:

YES to explore mistakes and learn from them (no to pretending no errors were made)

YES to act on what we learn about ourselves (no to “talking” and not “acting”)

YES to experience the discomfort of talking about ourselves (no to avoiding discomfort)

YES to explore our differences (no to avoiding our differences)

YES to work on our relationships with each other (no to working in isolation)

YES to act on what we learn about ourselves (no to “talking” and not “acting”)

The 40 planners said no to the status quo. They said yes to growing into something new, even if unknown. There is hard work ahead, and they will do it while practicing to find the balance between prescribe and enable as a community of professionals. They will learn how to work together better—so they can do better work with other people.

They are actively involved in their evolution. And their city’s evolution, too.

Reflection

What did you say “no” to recently—and what did it make room for?

What do you wish you had room in your life to say YES to?

What could you let go of to make room for that YES?