Prescribe AND Enable

I can see the scaffolding all of a sudden, the connection between two aspects of my work that have always felt far apart and unrelated. I see now that the distance is only on the surface.

An unusual city planner

I am an unusual professional city planner. I don’t write plans or policies. I don’t process development applications. I don’t have files in front of city council for decisions. I don’t have a constant team of planners and planner-types working with me or for me. And yet, I am in the room when the magic happens, when the sausage is made. I am a vital ingredient.

I am in the room when the planners land the big, simple question that changes everything for their project. I am in the room when developers, residents and the city’s planners start helping each other rather than work against each other. I am in the room when the impossible-to-find, game-changing, mind-bending cost-sharing formula for water pipes in old neighbourhoods is not only found but agreed upon. I am in the room when city council looks at the impossible made possible—and actionable.

Until just now, the planner in me has felt put aside for the last fourteen years, when I left the conventional planning world. Before fourteen years ago, I spent 17,000 hours in city council meetings. I watched the conflict, people not talking to each other or working things out, relying on elected officials to resolve their fight and then praise them or hate them for their decision. My resolve: we can do better than this. We can choose to do better than this.

“My resolve: we can do better than this. We can choose to do better than this.”

Something like facilitation

I’ve been on a quest to figure out how planners and the rest of city hall, citizens, business communities, and community organizations can work better together rather than fight each other. That other aspect of my work, which feels separate from “city planner,” is the work I do to support people as they have the conversations they need. Some call this facilitation, but it’s more than that. It’s not about getting people from A to B, but rather from where they are to where they are going, on their terms.

In my mind, facilitation implies getting a group to a predetermined destination. Instead, I support a group as they sort out what they want to accomplish and how they’ll pull it off. I “host” them. (Check out the Art of Hosting.)

As a host, I’m not bringing content to the conversation. I support them in their exploration of what they know, who they want to be, and what they choose to do together. This is the source of the separation I’ve been feeling: the city planner in me has opinions and ideas about how to make our cities better, while the “host of conversations” in me puts my views and ideas aside to best serve the group.

“The city planner in me has opinions and ideas about how to make our cities better, while the “host of conversations” in me puts my views and ideas aside to best serve the group.”

While hosting others, my opinions and ideas are not relevant or helpful; they muddy the waters, distract them from where they are going, and disable them from taking action they know best to take if given a chance to figure it out.

And then the scaffolding arrived.

While the above is true—that my work as a city planner and host of conversations are quite different areas of work—something else is too.

The scaffolding

The scaffolding appeared with two words that kept popping up in my world the last few weeks, always together: prescribe and enable. These words appeared in a quick debrief meeting after a gathering, flagging the prescribe traps we find ourselves in despite the efforts to enable fellow citizens, and when talking with a client about writing new zoning rules for a part of their city (and what they want to prescribe or enable). In a conversation with some colleagues, we noticed how people hate rules that prescribe what they can and can not do and resist the empowerment that comes when they are enabled to act as they’d like.

Let’s start with some definitions.

Prescribe

The Cambridge Dictionary defines prescribe, as a transitive verb, as follows:

To tell someone what they must have or do, or to make a rule of something (give rule)

To order treatment for someone, or to say what someone should do or use to treat an illness or injury (give medical treatment)

Enable

The definition of enable as a transitive verb, from the Cambridge Dictionary, has a different flavour:

To make someone able to do something, or to make something possible

To allow or make it possible for someone to behave in a way that damages them (psychology)

The Merriam-Webster Dictionary has another way of saying this: “to provide with the means or opportunity,” or “to make possible, practical or easy.” (NOTE: My use of the word enable here is not to encourage behaviour that damages people, rather to encourage new and healthy possibilities that would otherwise be absent.)

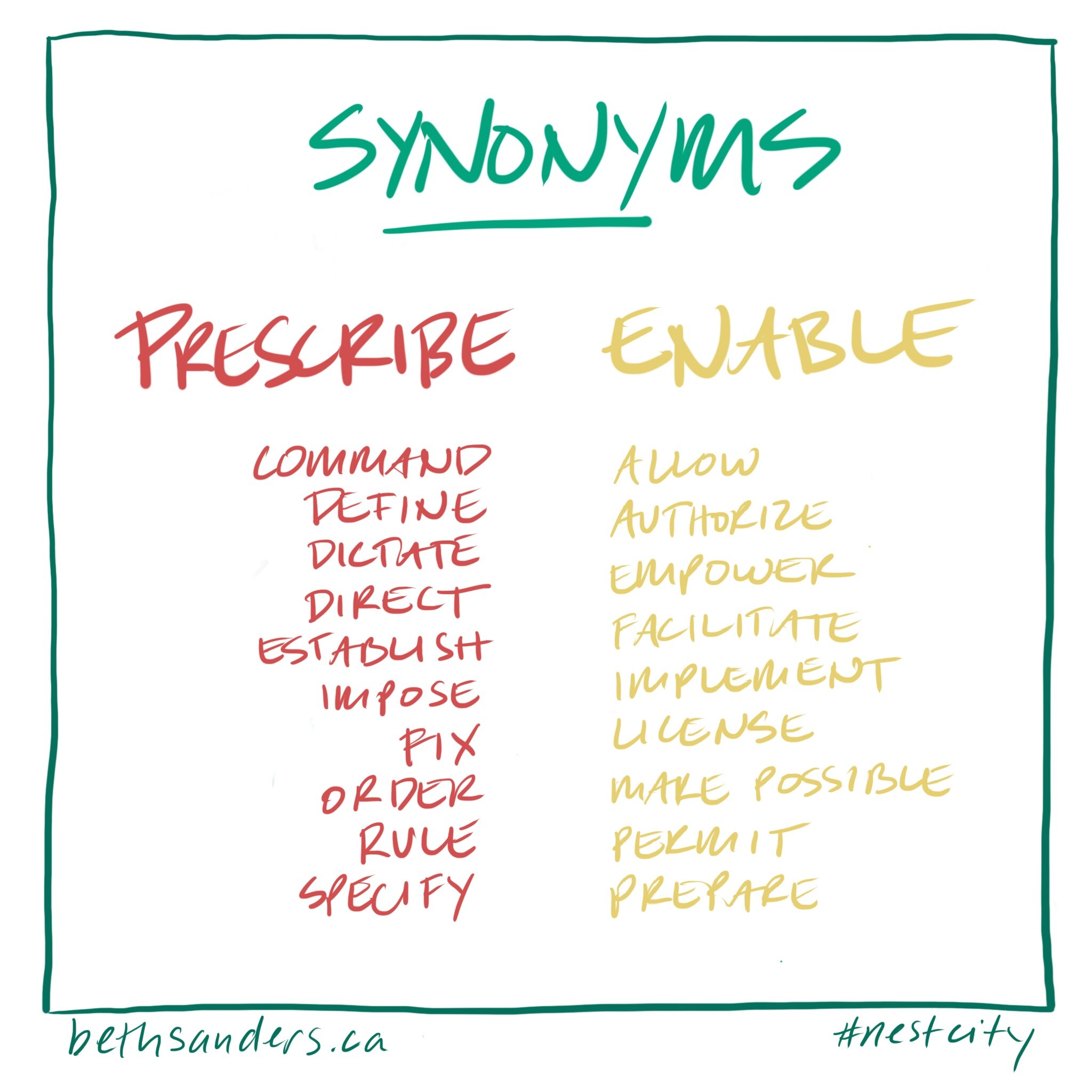

Synonyms

Prescribe and enable are words with different energies associated with them. Common synonyms for prescribe are: command, define, determine, dictate, direct, establish, impose, fix, require, rule, order, set, specify. Common synonyms for enable are: allow, authorize, empower, facilitate, implement, license, make possible, permit, and prepare. Where prescribe is about control, and what to stop, enable is about creating the conditions for something to happen.

Co-existing polarities

Prescribe and enable are not opposites; they co-exist, and they need each other to exist. Where prescribe is about structure and control, enable is about self-determination, self-organizing and empowerment. We recognize each of them because of the other’s presence or absence. There’s always a little self-determination and self-organizing when there’s a lot of control (it’s that spirit we have to push back and make the structure better), and there’s always a degree of structure necessary to enable self-organizing. One never exists without the other.

The question I always ask is not, “What is the right amount of structure?” I ask, “What is the minimal critical structure?”

Answering this question involves a series of Goldilocks questions: How much is too much? How much is too little? How much is just right? It always depends on the context in which we find ourselves.

Prescribe AND enable

We don’t have to choose between prescribe OR enable. We need to choose how much of each to suit the circumstances.

I often think of my kids when I ponder the degrees of minimal critical structure that enables self-determination or sovereignty. At three, wanting to enable them to make choices for themselves but recognizing they needed quite a bit of structure, I’d say, “You need to put on pants. Do you want to wear the blue pants or the red pants?” By the time they were thirteen, I let the structure lessen, and the self-determination grow: “You and I are making supper on Wednesday night. You decide what to make, I’ll get the ingredients we’ll make it together.”

Now in their early twenties, living with me while they go to school, they come and go as they’d like (though not so much with the pandemic!). My message now: “Let me know if you won’t be coming home at night.” I want them to have their own life, and I don’t need to know what they are doing, just as I wouldn’t know if they didn’t live with me. As a roommate who somewhat keeps track of their coming and going, I feel like a security system that serves as minimal critical structure for them to live their lives.

Finding the appropriate balance of structure and empowerment, of prescribe and enable, translates well to my facilitation work and the rules we put in place as we make our cities.

A participatory “test”

A group of community organizers asked me to help create space in a gathering they were planning for attendees to exercise their participatory leadership. After some presentation time (some needed structure to frame what was to come), they wanted people to explore the ideas they’d like to try—and connect with others who wanted to explore similar ideas. They wanted to create the conditions for people and ideas to find and meet each other.

I noticed that the process they were designing was not participatory.

Here’s a quick three-part “test” I apply:

Is most or all of the time focused on the words of few people or many people?

Are the topics, tasks, activities determined by organizers or participants?

Are the people we work with decided for us, or do we choose for ourselves?

In an instant, I can spot when a participatory intention and the process design are at odds. With this group, two aspects of their design were working against them. First, about 75% of the time was allocated for attendees to sit and listen to a handful of people. While some of this was necessary to get people on the same page, it was not all necessary. Second, they had predetermined topics for people to choose from as break-out sessions.

Despite a stated intention to create a participatory event, they erred on the side of more structure than needed, prescribing who would listen to who and what they would talk about. These organizers recognized these inconsistencies as soon as I named them; they needed my help to put their finger on what felt “off.” It’s hard work to stay on track, especially when we are so well conditioned for lots of structure. They had drifted away and needed a nudge to get back on track.

Zoning to enable

In a whole other setting, I am working with a group of city planners who are rewriting a zoning bylaw, the rules that dictate how big buildings can be, how close they can be to property lines, what can happen in those buildings or out on the land. They are in a big question: what to regulate and what not to regulate.

It takes me back to my first years as a development officer in Brandon, Manitoba, and rewriting a much smaller zoning bylaw. We were shifting from a prescriptive bylaw to one that would establish performance standards instead (as in, “if you meet these criteria, you’re good to go”).

The shift was significant. The city moved from prescribing specific activities to enabling activities that met certain criteria. For example, the old bylaw laid out a five-page list of what businesses could sell in a retail store. In the late 1990s, a “record store” was allowed, but there was no mention of a store that sold only CDs. It was so specific the bylaw no longer accommodated what was happening in real life. We changed a five-page list of commercial uses to a half-page of relevant performance criteria (like enough parking, for example).

Here's the shift: we no longer worried about what was for sale. We focused instead on whether the location made sense for retail in the city and if there was enough parking. Other laws and the police regulate if what is for sale is legal. After an applicant met the basic criteria, our message was, “do your thing!”

Look for “just right”

Too much prescription leads to confusion, and too little prescription leads to incoherence. In every instance, context and life conditions will tell us when to add or remove structure. We’re looking for “just right,” but there’s no recipe. There’s no prescription.

Too much prescription leads to confusion

Too much prescription leads to unnecessary clutter that confuses everyone. When someone is setting up a business and is looking for a location, they have to find a building that is zoned correctly. Would you rather look through five pages of tiny text to see where your business fits (only then to look for that kind of land), or just look for retail property?

When you’re looking to meet with and connect with people who want to work on your funky new idea, would you rather leave it to chance that you’ll find them in a room of 80 people or find and meet them?

Too much prescription is limiting. Whether we are trying to say what kinds of businesses will work on a city street or what people will talk about when they get together to work on a project, we can halt initiative and improvement. Too much prescription constrains our efforts to improve our cities.

Here’s the contrast:

We’ll tell you what you can do or talk about; choose from this list, or

Get creative and do what you want (within these reasonable constraints)

Whether a zoning bylaw or a facilitation assignment, this contrast is the same.

Too little prescription leads to incoherence

When there’s too little prescription, our experience is confusing, wobbly, and lacks coherence. At the scale of a city, it’s hard to plan our infrastructure investments without some kind of plan. That’s a form of stability and coherence we seek for our shared financial investments as taxpayers. And a meeting always works better with some structure around a clear purpose for the meeting. Without an agenda, a meeting is confusing and incoherent.

Too little coherence is also limiting. If a city government is indecisive about the rules it puts in place to guide development, the business community's contributions to our economic well-being are held back. Or people don’t have clear information to choose where to live.

Here’s the contrast:

Go do or talk about whatever you want, or

Get creative and do what you want (within these reasonable constraints)

Whether a zoning bylaw or a facilitation assignment, this contrast is the same.

Start with a simple question (or two)

We don’t have to choose between prescribe OR enable. We need to choose how much of each to suit the circumstances. I recommend starting with a simple question. The go-to question that I ask all the time is: What is the minimal critical structure needed to enable ______?

Sometimes it helps to look forward and imagine a range of ideas or actions you’d like to enable, and then cast back to explore the structure question. What ideas and tangible improvements make people feel alive—that’s what you want to enable. The other simple, helpful question: I ask all the time: What do we choose to enable?

Notice the resistance

Identifying the minimal needed structure, and putting it in place, is hard work because we must let go of familiar structures that feel comfortable. We have to let go of the perceived comfort and control that comes with telling people to talk about what we want them to talk about. We have to let go of the perceived comfort and control that comes with telling people precisely, for example, what businesses can locate where in the city.

Even when we know we want to do or allow something new, and that less prescribing is required, it’s hard work. We might even tell ourselves it’s not worth the effort and sabotage our efforts. Others will want us to go back to the old ways, too; they will tell us they are confused because they want the familiarity of the rules and prescriptive details. We all do this, even when we say we do want things to be different. It is important to notice our resistance. Especially the subtle kinds of resistance that pop up when we feel we’re on track.

Two resistance patterns

In a conversation with a couple of colleagues last week, we identified a significant conundrum: we often love to hate rules, and we often resist empowerment. When rules prescribe what we should do or how we should act, it can feel good to have something to fight about. Maybe we secretly don’t like how we feel constrained in one area of our life, so we blast the rules in another area. Or we fight because we don’t like the constraints, not realizing that fighting will not make many constraints go away. (For example, while I might not like living within planetary constraints, not liking this will not make the constraints go away.)

In contrast, the empowerment that comes with fewer rules means we need to increase our personal responsibility. It’s no longer an easy option to blame others when things don’t work out or an easy option to be the victim and blame others for not having been rescued.

Choose a balance that enables new possibilities

Our default is to imagine everything that could go wrong and put rules in place to handle all those negative eventualities. This is a form of resistance against newness, against what’s possible if we choose to make improvements to our city. While it is a good practice to think about what could go wrong and test if the rules will have the outcomes we want, focusing only on what could go wrong gets us more of what could go wrong. To improve the world around us, we must enable ourselves to enable new possibilities.

Choosing to enable new possibilities requires self-examination. When I notice the fighting within myself, I can recognize it as an indicator of my inner desires for improvement. When I feel constrained, it is an indicator that I’m looking for empowerment and self-direction. When I feel confused, I’m looking for clarity. Once I know this, I can act accordingly in my personal world. Our actions in the personal world add up to actions in the wider world of the city and beyond.

“When I notice the fighting within myself, I can recognize it as an indicator of my inner desires for improvement.”

In the end, looking at what motivates me to want control, to want to prescribe, will allow me, and those I’m working with, to find the amount of prescription that best suits the context. (Do I need to feel powerful when I feel powerless? Do I need to make sure there is someone to blame other than myself?)

Understanding myself and my resistance, I’ll get out of the way of the group I’m hosting to go where they are going, and I’ll get out of my way as I work to be the best city planner I can be.

Reflection

What makes you comfortable about the structure that comes with prescribe and the self-organization that comes with enable?

What makes you uncomfortable about the structure that comes with prescribe and the self-organization that comes with enable?

When you get into “fight mode” out in the world, in what ways are you fighting to ignore the tension you feel in yourself about your personal circumstances? And when are you fighting in the outside world because it is your work to do?

What possibilities would you like to enable in your city—and who do you need to be to enable those possibilities?