City Making With Women

Less than an hour before I took the stage last month to talk about building cities for women, with Imagine Cities in Calgary, I heard that I came in second for the chief planner position with a North American city. I heard the words: “It was a tough decision. It was really close.” And then I heard the words: “He has…”

It was a close race between a woman and a man, and they chose the man.

I received the news and turned around to get ready to meet my commitment to the event host, Imagine Cities. I had to show up in a public place and talk about building cities for women. Here’s a bit of what I said and what I didn’t say.

A note before you continue: I choose to keep people’s names and the city government confidential. This piece is about symbolism and how the choice made played out within me in the days that followed. I do not question the decision or shame decision-makers. I intend to shine a light on this pattern: It was a tough decision. It was really close. They chose the man.

Qualifications

Before we took the stage, my stage mates and I were joking about something that isn’t a joke: we, as women, don’t feel qualified to talk about building cities for women.

The “we” here: Lorelei Higgins has an MBA, is the Indigenous relations strategist with the City of Calgary and is a leader in the City of Calgary’s pandemic response team; Reachel Knight has a BA, is a business strategy coordinator at the Calgary Parking Authority and is a leader in understanding parking and traffic in city planning in Toronto and Calgary; and me, Beth Sanders. (I have a Master of City Planning, have worked as a city planner for 26 years and have written a book, Nest City, about the complexities of city building.)

And our gracious male host, Ron Jaicarron, pointed out to us, “You are women! You ARE qualified!”

What I did not say about qualifications

And still, we joke when there is nothing all that funny.

What is going on when three women, well into their careers and proven to be capable, need an outsider man to tell us that what we have to say is legitimate? What is going on within us?

What motivates me

Two things motivate me as I make my way through the world. First, I want to make the best possible contributions to the world. The result is that I choose work that feels good to me, to my soul and to who I am deep inside. Second, from the outside, what motivates me are the words “you can’t do that.” I hear those words, even as a subtle message, and I want even more to do “that.”

I’ve learned that when the outside world says, “you can’t do that because you have a female body,” or, “you have to do this because you have a female body,” I bristle. I’ve learned I do not always have to respond to what the outside world says, that I can choose to do what I want when I want. And it is important to say that “X” is not ok because of the body I find myself in.

What I did not say about my most recent experience with my female body

This is factual:

It was close. It was a tough decision.

They chose the male candidate over the female candidate.

The woman not chosen (me) goes on to a speaking engagement about building cities for women and leaves this experience out of her story.

I wish I could think faster on my feet and had relayed this experience on the stage.

Am I a feminist?

Labels help us identify our group: people like us and not like us. They serve as a rallying cry, energy to gather, strength to resist. A label is healthy when it helps us understand ourselves or others, yet unhealthy when it feeds fight energy.

I duck out of the debate about whether to label myself a feminist. Instead, I ask, “What if we stop judging ourselves by the label we use, or don’t use, just as we do not want to be labelled by the body we have?” Instead of focusing on debate about the label, I pay attention to what matters: gender equality and gender equity. If that means the label applies, that works for me. If not, that also works for me.

What I did not say about gender equity

At that moment on the stage, I failed to acknowledge how easy it is for our city systems to stay in the familiar and comfortable and pick conventional men to serve as decision-makers. The ease is not unique to government; it applies elsewhere as well.

Gender equity doesn’t mean choosing me because I am a woman. It means that when a decision is close, take a closer look at what’s happening. Horizontally, look for gender equality with lateral positions. Vertically, look at who leads the planning profession, who has served this city in this way before. In this case, only white cis heterosexual, middle-class men have served in this position for decades.

“It is for our city systems to stay in the familiar and comfortable and pick conventional men to serve as decision-makers.”

White women

Here’s an operating principle I am learning to live by: if someone says something is not working, I need to trust and believe that experience. I don’t need to understand. Rather, I have a choice to make to trust and believe. If I wait for when I understand others’ experience, I might not reach that understanding soon enough, or at all.

When Indigenous women, Black women or women of colour say they are not represented, not heard, not involved or included, then they are not. I have hard work to do to recognize the insidious nature of the mistrust and disbelief that operates in me.

What I did not say about white women

As I took the stage, all I knew was that the person chosen over me was male. I did not know the colour of his body. I hoped he was not white. As a white woman, I intend to make space for women and men of colour to step into leadership positions.

City building

The cities we build represent the societies that create them. In North America, white, cis-gendered heterosexual, middle-class men build our cities with a limited and exclusive view and experience of the city. My experience as a white cis middle-class woman is also limited.

The post-war neighbourhoods of North America were designed for the traditional nuclear family: dad, mom, kids and one car. Dad took the car to work, leaving mom and kids stranded in neighbourhoods designed for movement by car. Eventually, many nuclear families ended up with two cars, mom working.

We design the transportation system in North American to cater to nuclear families with two cars. If you have different relationships and household shapes, then the system we make to move around doesn’t suit you. And if you don’t work conventional office hours, the public transportation system also doesn’t work for you; it best serves the people moving in the morning and late afternoon.

What I did not say about city building and women

On the whole, we continue to put the head of the nuclear family at the head of our cities’ planning departments. We do this everywhere.

What I now know: the chosen man is white.

“We design the transportation system in North American to cater to nuclear families with two cars. If you have different relationships and household shapes, then the system we make to move around doesn’t suit you.”

Building infrastructure to better serve women

It is always important to be clear about the purpose of infrastructure. Does the infrastructure serve certain people? Is it designed to serve white, cis, heterosexual, middle-class men? Or nuclear families?

Are there multiple purposes, for different groups of people? What if we designed for these various purposes and tested to see if the design meets those purposes? We would have to ask and involve people other than the standard man. And with that new understanding, we need to organize ourselves to use what we hear. We have to do something about what we hear, even when there is resistance within ourselves and others.

What I did not say about infrastructure and women

As far as I can tell, the chosen man is capable. I trust that he was chosen because he is capable.

In this larger pattern, however, when a tough decision between a man and woman usually ends up with choosing the man, there’s a part of me that wonders, “Do I just not fit the mould? Did I lose out to convention?”

I trust the choice made, and I’m not asking for the decision to be revisited. Yet, a larger pattern has my attention. When we want to change who we imagine the “user” of the city to be, from white, cis, heterosexual, middle-class men to multiple other perspectives, we are best not to place those same white men in decision-making positions at city hall.

“When we want to change who we imagine the ‘user’ of the city to be, from white, cis, heterosexual, middle-class men to multiple other perspectives, we are best not to place those same white men in decision-making positions at city hall.”

We devalue the voice of women in city decision making

It is easy to identify how we devalue the voices of women. It comes down to who we hire, who we place in positions of power, options for public engagement are in locations or times of day that don’t work for women or don’t provide childcare. Or there can be a sense of superiority in decision-makers, assuming that they are best suited to make decisions for others.

It is harder to get at why. We don’t want to upset the power arrangement. White men and women want to keep the power they have. Even white women, who do not come out on top, have power in the current system. We—I include myself in this—understand the rules of the game, and we don’t want the rules to change.

What I did not say about the voice of women in city decision making

The person who chose the white man was a white woman. Four of the five interviewers were white women, the other a white man. I recognize this in myself, as a white woman: to propagate the power structure as it is, where we know the game and have found our way in it, we reinforce the power of white men.

(Again, I am not asking for a different decision. My intention here is to point out a pattern.)

Advice to leadership

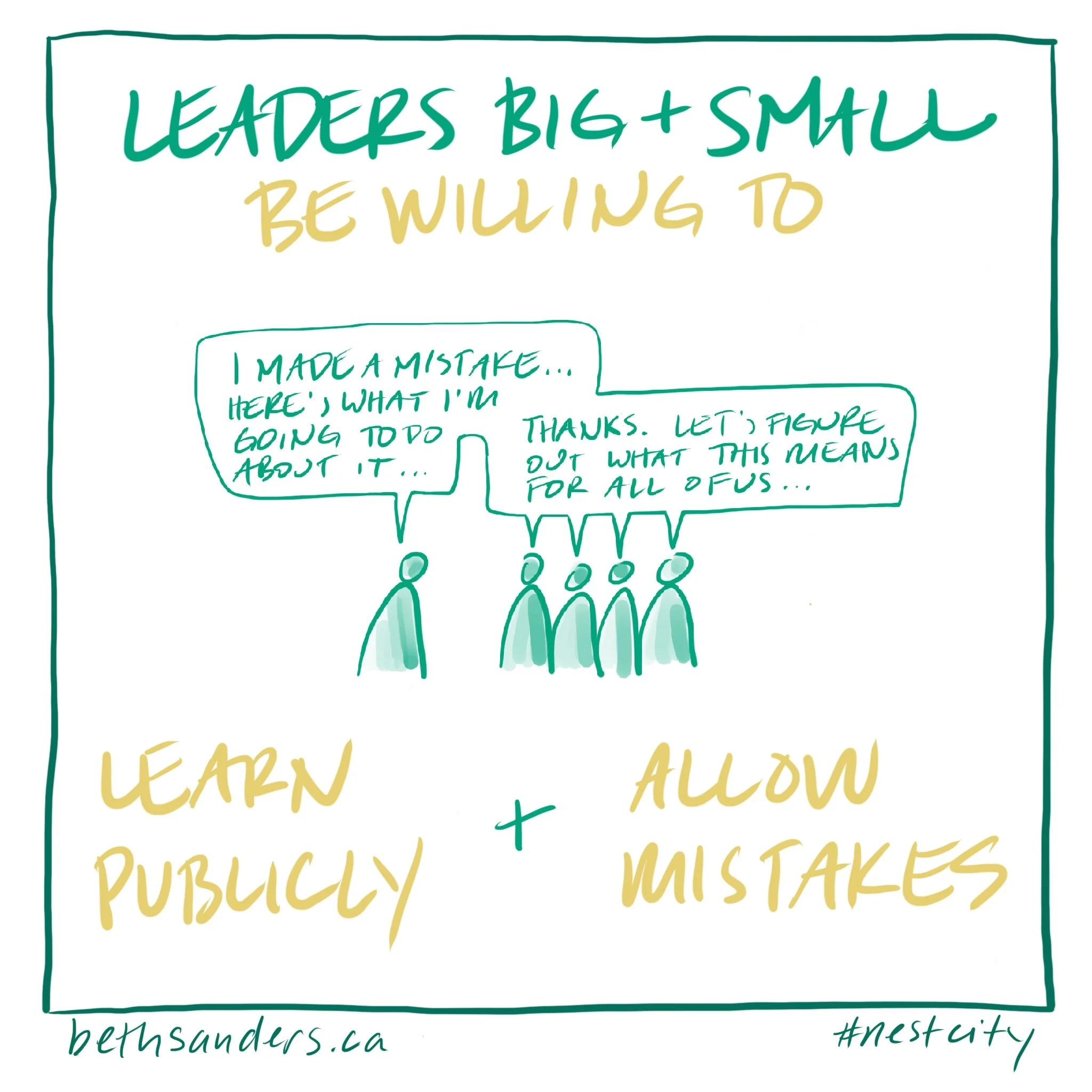

To the “Capital L” leaders, in formal positions of power: don’t imagine you’ll get it right all the time. Cities are never-ending improvement projects, and leaders will make mistakes. Be willing to learn publicly.

To the “small l” leaders, the citizens of any gender: allow leaders to make mistakes and learn from them. When the mistakes are really bad, say so, but give them space to make mistakes, learn, and make the needed improvements. They’ll then be more likely to work for those improvements we want.

What I did not say about leadership

Leaders should look like the people they lead. Symbolically, I am a white woman left out. If I am left out, then who else is?

Here I am, back at qualifications and a story told beside me on the stage. A white Canadian man, with good intentions, is looking for an Indigenous woman with a Ph.D. to teach. He complains about the lack of Indigenous women with PhDs without understanding the root causes. School is not a comfortable experience for many Indigenous people due to the genocidal efforts of colonial England and the Government of Canada through residential schools. Further, for almost one hundred years, Indigenous women lost their Indian Status when they achieved college education (read about Indian Status at the Canadian Encyclopedia.) Further, the assumption that an Indigenous woman needs to have a Ph.D. to be knowledgeable and fully capable of teaching the material is colonial. The “Ph.D.” convention gets in the way of the objective: including Indigenous women in the teaching world.

I wonder about the conventions are we so attached to that we can no longer see how we are limited and bound by those same conventions.

City making by women

At one point on the stage, I distinguished between city building and city making. “City building” is a masculine endeavour, the physical world we build outside our bodies. In contrast, “city caring” tends to our citizens’ needs. This quality of care, of social wellbeing, is a feminine endeavour that looks after the world inside our bodies and our relationships.

City building and city caring are not the work of men and women, respectively. I use the words “masculine” and “feminine” on purpose, for they are qualities we all possess. For example, I have a female body and, in many ways, feel more masculine than feminine.

City building and city caring are not the same things. But something magical happens when we put them together: city making.

What I did not say about city making

Let’s unpack the event’s title, “City Building for Women.” The masculine “city building” is in play, and the word “for” denotes a separation, perhaps a superiority. City building works on behalf of others, on behalf of women.

Let’s try some other language on for size:

City making WITH women

City making AS women

City making BY women

It’s not about the label. It’s about the purpose of the endeavour. If the purpose of city making is to make cities that serve citizens well, then we need to include far more than we can begin to imagine.

City making by Indigenous women

City making by Black women

City making by trans women

City making by immigrant women

City making by newcomer women

What do you imagine?

Reflection

How and where do you feel belonging in your city?

Which gender and cultural groups are easily included in community decision making?

Which gender and cultural groups are easily overlooked, or rejected, in community decision making?

What do you plan on doing differently to reach out and include others, not like you, in tiny or large community decisions?

Click here for a recording of Building Cities for Women, hosted by Imagine Cities.