Listen at Scale

I bet this is a familiar experience: someone says they want to hear what you think and they do most of the talking. It can be with a family member or partner, or boss or colleague, or out in the communities you live and work in. If you are like me, you also do it yourself. Even when we don’t mean to, we fall into the trap of telling when we mean to be listening.

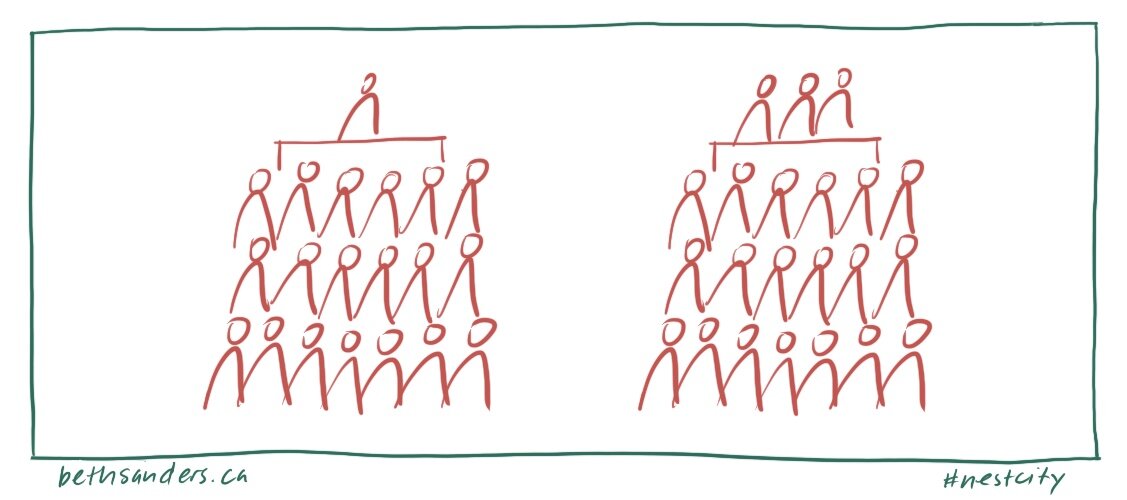

Telling and following

This is what we are most familiar with: a designated person speaks to a group and the group is expected to listen. This is a “telling” shape of communication exchange.

A “telling” shape of conversation: the panel, or theatre

There is nothing wrong with the telling shape in the right circumstances. For years, I’ve used the example of a doctor friend whose expertise is infectious diseases. Her role in the health care system is to serve as a resource for front-line doctors. She has knowledge they don’t have because of her specialization and they need this knowledge in their work; when something strange surfaces in their pratice she tells them what they need to know. While there is room for questions from front-line doctors to understand what she is telling them, they trust the information she conveys, take it and use it in their practice. My friend is in the telling role while the front-liners listen and follow, trusting she has knowledge they need to do their jobs well. The telling format makes perfect sense. (And yes, she’s busy with COVID-19.)

Here’s the catch: this is our default way of being with each other and it is mutually reinforcing. Someone has something to tell and the rest of us expect to be told.

“Someone has something to tell and the rest of us expect to be told.”

We are most familiar with two shapes of telling: the board table and the theatre. These shapes, and our behaviour in these shapes, is about expertise and power. At the front of the room, or at the head of the table, is the one from whom we expect will tell us what to do, the boss or the expert. One person has the answers and the rest expect the answers. One person knows what to do and the others will make it happen.

Another form of “telling” conversation: the board table

These are shapes for telling and following, for providing and receiving direction.

We all participate in these shapes: the boss/expert expects others to follow and the subordinates have steep expectations of the boss/expert. The boss will say how things will unfold. Subordinates expect clear directions.

Listening at scale

Listening is a crucial part of telling and following. The subordinates, or the audience, are there to listen and are expected to listen. Even when the audience is a group, this is listening as an individual to an individual: I hear what the boss/expert has to say, I take some notes, and I will adjust my actions as dictated. Even if there are many people listening, we are listening as individuals to an individual.

“Listening as an individual to an individual: I hear what the boss/expert has to say, I take some notes, and I will adjust my actions as dictated.”

Listening at scale means listening to more people in three ways:

Listen as an individual to more voices

Listen as a group to more voices

Listen as a group to the group

The shape of a conversation shifts dramatically if the gathering has a purpose other than telling and following. When we intend to explore collectively, to figure out a way forward together, the shape shifts to circular, where the expertise and contributions of everyone–-rather than one or select few–-are welcomed. The listening is done by individuals and the group because the purpose of the conversation is about collective discernment: we have something to figure out together.

Shift the shape when we have something to figure out together

Both shapes are appropriate depending on the intentional purpose of a gathering.

“Collective discernment: we have something to figure out together.”

A telling and following shape is perfect for my doctor friend, and yet shapes that foster listening and discernment are the right choice in other circumstances. A city planner colleague of mine is working to create a new set of rules to guide infill development in his city and he recognizes that there are people with different perspectives on this that need to be taken into account: other people in city hall, builders and developers, and citizens and community organizations. He recognizes that they all have pieces to the city-puzzle we are making. He needs to listen to them all and he recognizes that as these different perspectives listen to each other, better solutions come forward. He offers, around little tables and within the whole group, ways for people to listen to each other and find ways forward that look after a wide range of interests. This tangibly helps him in his work and it enables everyone else make a city that serves them well.

These shapes are right in the right time and place. It all depends on the purpose: telling or listening, direction or conversation. And in many gatherings it can be a combination of both, so knowing the purpose of each part of the agenda is vital, to minimize confusion. For example, at the start of a meeting this week the convenor will say, “We are here to talk about the next phase of implementation of our mental health plan. We are not here to revisit the principles and objectives of the plan.” The convenor will tell us the boundaries of our conversation, then we will shift into listening mode to discern the best possible actions.

5 questions to discern purpose

Here are five questions I use to figure out what shape makes sense for a meeting:

What is the purpose of the gathering?

What needs to be told and who needs to tell it?

Who will be listening and to whom are they listening?

What are we listening for?

What is the shape that serves the purpose?

These questions can be used at scale, too. For a whole community engagement program, for particular gatherings or audiences, or for discreet activities within a gathering.

REFLECTION

What shapes of conversation are you most comfortable with as a host?

What shapes of conversation are you most comfortable with as a participant?